TLDR: RISCV’s memory management model, SV32 and SV39, two page based virtual memory architectures. Understand how multilevel paging works, why it is needed, and why it is better.

Background

So why do we need a virtual memory system at all? Why not just let programs directly access physical Memory?

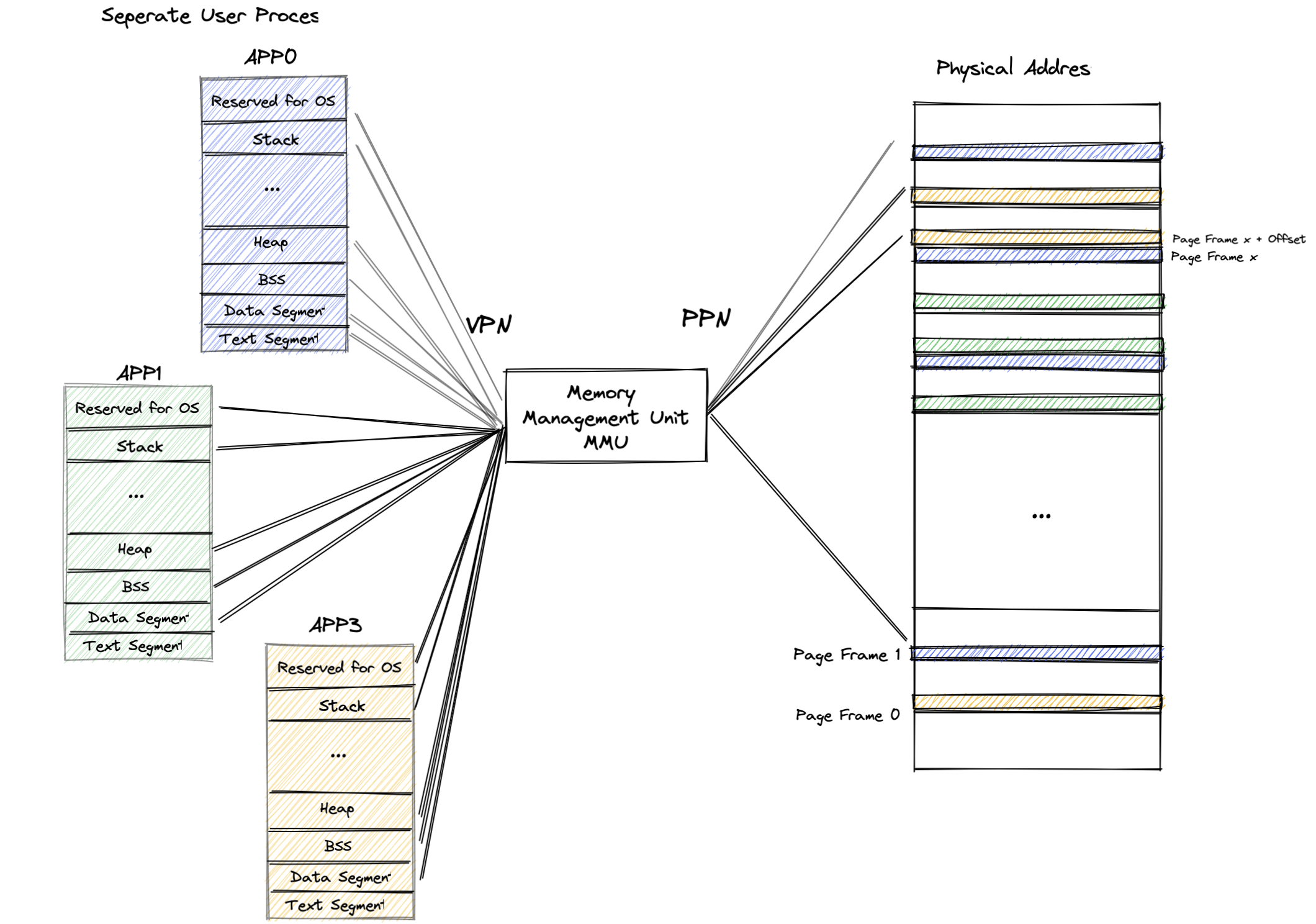

From the perspective of applications (that is, app developers), they monopolize the entire CPU and a specific (continuous or discontinuous) memory space. But, as a system, we don’t allow exclusive CPU usage by any one app. Therefore, the application’s own exclusive CPU is just an illusion that the kernel wants the application to see, an abstraction that is hidden and invisible to the application. Basically, to each application, “they each have their own memory and cpu”, however, in the eyes of the OS kernel, they don’t. This is known as virtual address mapping.

If an application were to directly access physical address, some of the following problems would occur.

- An application would need to plan the address where it will be loaded (to run) at the time of its creation. In order to avoid conflict, this will require app developers to negotiate this, which is obviously an unreasonable.

- The kernel does not protect the access behavior of the application, and each application has the right to read and write the whole piece of physical memory. Even if the application is limited to running at the U privilege level, it can still cause a lot of trouble: for example, it can read and write data from other applications to steal information or disrupt its normal operation; it can even modify the code snippets of the kernel, resulting in the execution of malicious code. In short, this makes the system both unsafe and unstable.

- The memory use space of the application is limited before it runs, and the kernel cannot flexibly provide the runtime dynamically available memory space to the application. For example, after an application is finished, the space occupied by the application is released, but this space cannot be dynamically used by other applications that are still in operation.

Therefore, in order to prevent application from misbehaving, we would need a method to better manage and access physical memory. We would need to provide the application with an abstracted, more transparent, easy-to-use and secure memory interface. This is the purpose of memory management models.

SV39 Memory Management Model

RISCV has three popular memory management modes. These are the Sv32, Sv39, and Sv48. First, we will introduce the memory management model under the Sv39 architecture.

Paging

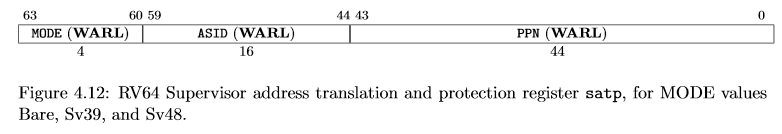

Paging is a system by which a piece of hardware, commonly known as MMU (memory management unit), that translates virtual addresses into physical addresses. The translation is performed by first reading a privileged register called the SATP (Supervisor Address Translation and Protection register). This register turns the MMU on/off, sets the address space identifier, and sets the physical memory address where the first page table can be found. It’s quite important!

Thus, the paging process converts a program’s own virtual addresses to physical addresses.

Satp Register

We just mentionde the SATP register, so how what does it do exactly?

All translations begin at the Supervisor Address Translation and Protection (SATP) register. We can see that the PPN (physical page number) is a 44-bit value. However, this value has been shifted right by 12 bits before being stored. This essentially divides the actual number by 4096 ($2^{12}=4,096$). Therefore, the actual address is PPN << 12.

The ASID, or Address Space Identifier is used to reduce context switching overhead.

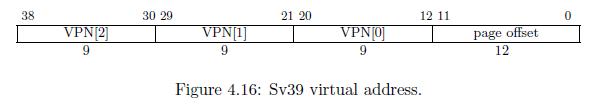

Virtual Address

The Sv39 virtual address contains three 9-bit indices. Since $2^9 = 512$ , each table contains exaclty 512 entries, and each entry is exactly 8-bytes (64-bits) as shown below. The Sv39 virtual address contains VPN[x]. The VPN stands for “virtual page number”, which is essentially an index into an array of 512, 8 byte entries. So, instead of having the virtual address directly translate into a physical address, the MMU goes through a series of tables. With the Sv39 system, we can have one to three levels. Each level contains a table of 512, 8 byte entries.

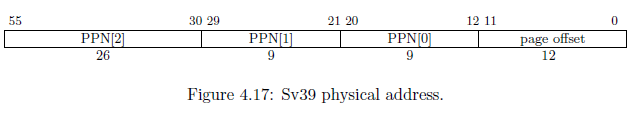

Physical Address

The physical address is actually 56-bits. Therefore, a 39-bit virtual address can translate into a 56-bit physical address. Obviously, this allows us to map the same virtual address to a different physical address–much like how we will map addresses when creating user processes. The physical address is formed by taking PPN[2:0] and placing them into the following format. Laslty, the page offset is directly copied from the virtual address into the physical address.

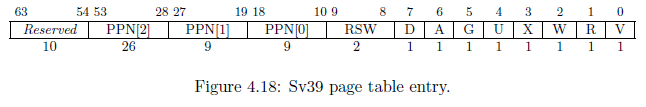

Page Table and Table Entries

A table entry is written by the operating system to control how the MMU works. Notice how the length of the physical page address, {PPN[2], PPN[1], PPN[0]} is the same length as in the physical address.

Structure

Now lets see how everything comes together, below is the Sv39 paging system in RISCV.

We can see that the first page table starts at the SATP address, and the VPN[2], VPN[1], VPN[0] labeled L2, L1, L0 respectively are used as index for each table layer. We also see how the offset in the virtual address is directly used for the physical address.

One Level, Two Level, and MultiLevel Paging

After being introduced to the Sv39 architecture, lets understand more about the paging system. Here we discuss three different paging architectures.

One Level Paging

This is the most straightfoward paging architecture, esentially a one to one mapping from virtual address to physical address.

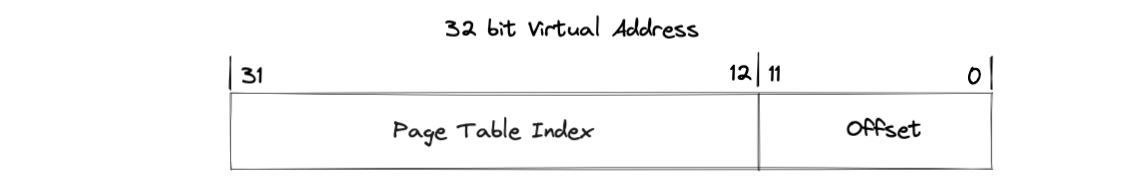

Structure of Virtual Memory

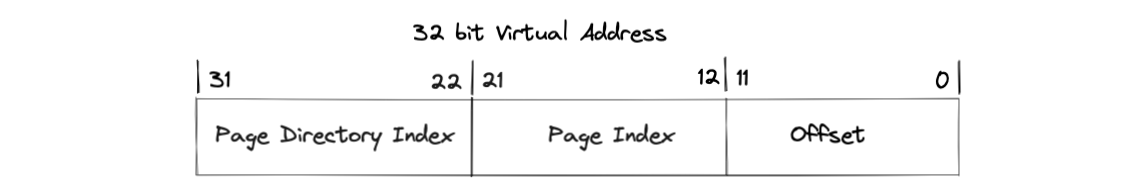

Let’s consider the following structure for a 32 bit virtual address, which is mapped to a 32 bit physical address.  Given a 32-bit virtual address space, we can have a total of $2^{32}$ = 4GB address space. Looking at the offset, the size of a page is $2^{12}$ = 4KB. Then to get the total number of pages that our address space can hold, we just divide the two values, a total of $2^{32} / 2^{12} = 2^{20}$ pages. This confirms our virtual address structure.

Given a 32-bit virtual address space, we can have a total of $2^{32}$ = 4GB address space. Looking at the offset, the size of a page is $2^{12}$ = 4KB. Then to get the total number of pages that our address space can hold, we just divide the two values, a total of $2^{32} / 2^{12} = 2^{20}$ pages. This confirms our virtual address structure.

It is important to understand how to break down a given virtual address structure!

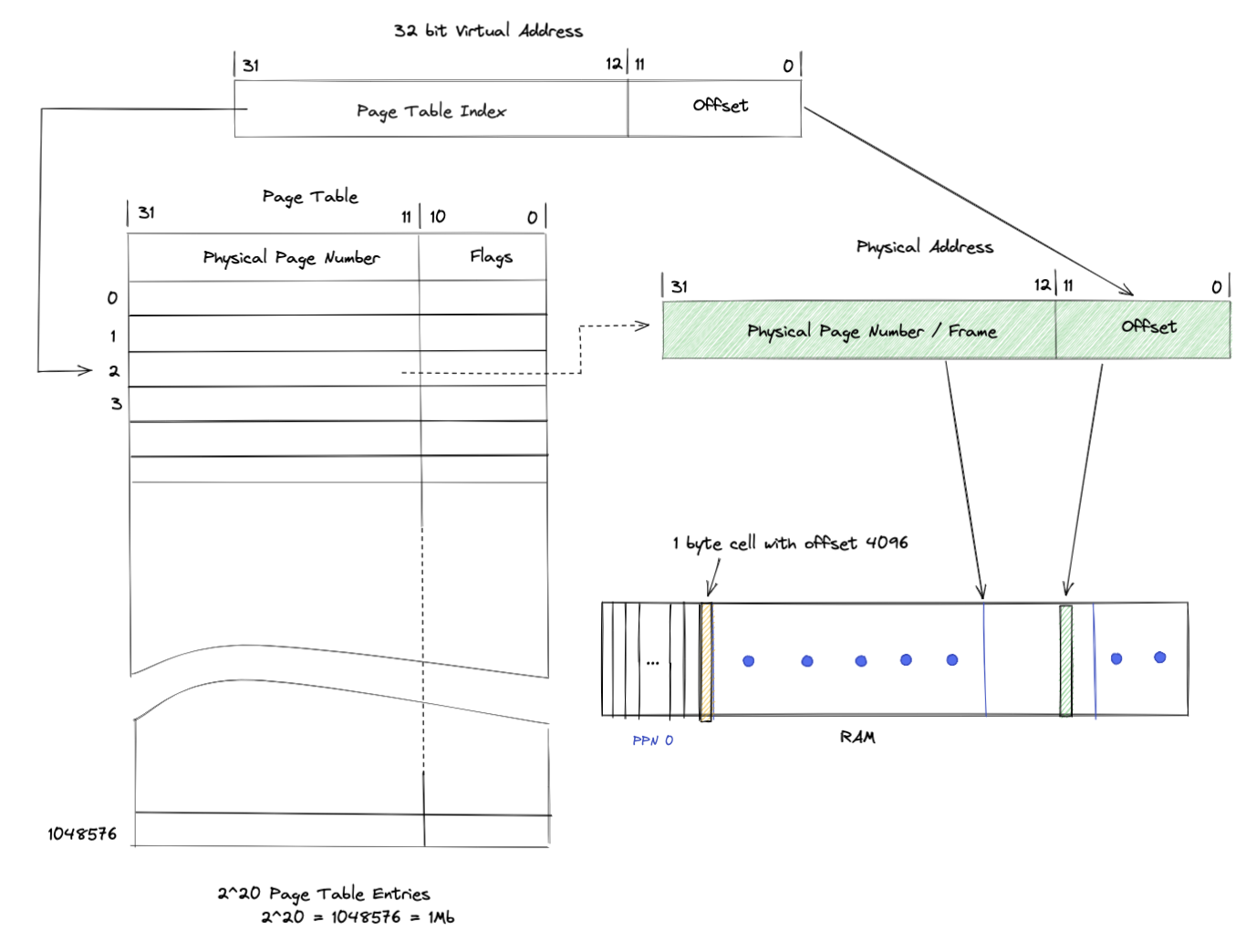

Structure of Table

The highest 20 bits of our virtual address will represent the indices of our page table, which means our page table will have $2^{20} = 1048576$ entries, or 1MB.

- Each entry contains a frame number. Since there are $2^{32}$ physical addresses divided into frames of size $2^{12}$, and assuming frame size == page size, we can see that there are $2^{20}$ frames, so we need 20 bits to store the frame number.

- Then we need some flag bits, such as dirty bit and valid bit, also for segmentation, we need read, write, execute permissible bits (just like in our SV39 architeture).

This gives us a paging architecture that looks something like this

Required Memory

This gives a total of 25 bits per entry. Lets round this up to 32 bits, or 4 bytes for easy math. Thus, the total size of the page table would be $2^{20}$ entries x $2^2$ bytes/entry = $2^{22} = 4194304 =$ 4MB for a single table.

4MB of contiguous space per program is a lot. Moreover, if the process is only using a small part of its address space, we should only need to access a small part of the page table. But in a one-level page design, we will have to store/load all 4MB of the table.

Just as with the address space, we can solve these problems by paging the page table itself. Lets look at two level paging.

Two Level Paging

In fact, 80x86 and RISCV SV32 use a two level paging system

Structure of Virtual Memory

Still using a 32 bits, we can define the virtual address as such.  Here, our page size is still $2^{12}$, but the upper 20 bits have been split into two equal sizes of 10.

Here, our page size is still $2^{12}$, but the upper 20 bits have been split into two equal sizes of 10.

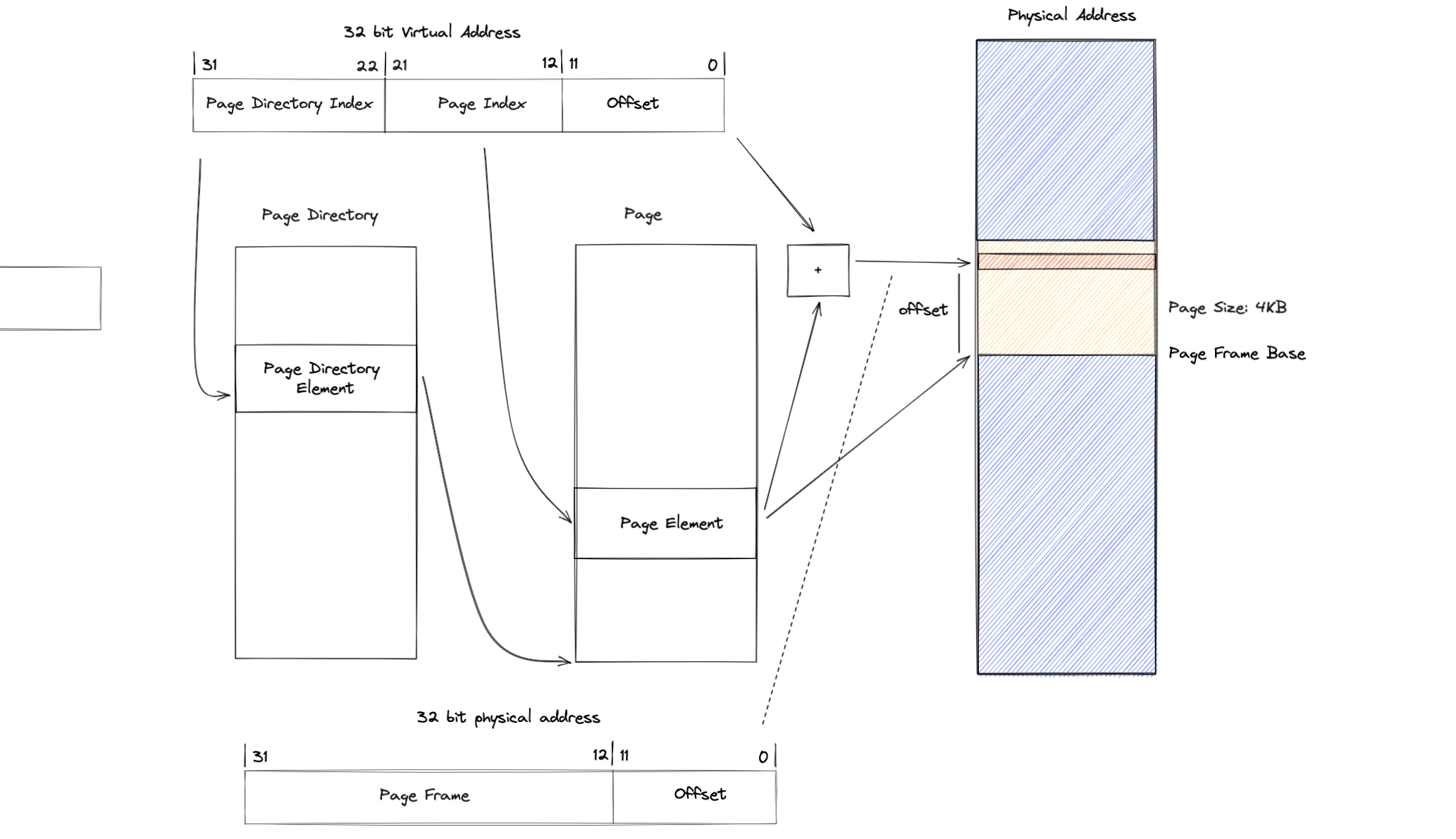

Compared to the one level paging system, now the translation to physical address takes 2 steps.

- The highest 10 bits is used as the index for the first level table, also known as page directory table.

- The next 10 bits is used as the index for the second level page table.

Structure of Page Table

Both tables have $2^{10}=1024$ table entries. However, the table entry sizes may be different here, since, only the entries of our second table needs to contains a 20-bit address corresponding to our physical page frame. The figure below shows the transition process.

The 10-bit higher logical address is used to index the page directory table to get a pointer to the relevant second-level page table. The middle 10 digits of the virtual address are used to index the secondary page table to obtain a higher 20 digits of the physical address. The 12-bit offset of the virtual address is directly used as the lower 12-bit of the physical address, thus forming a complete 32-bit physical address.

Required Memory

Memory usage by page tables isn’t always better when using multilevel paging.

Okay, so why might a two level paging system be better? Lets say that we want to access up to 1MB of contigious data, or 1024KB, starting from 0.

For a one level paging, we can have to load all $2^{20}$ table entries. Although it is able to map this space, our table size will equal to the (number of entries) * (page entry size), which is 4MB.

With two level paging, however, we can be more precise about what to load into memory. According to the subdivision of the virtual address, our first level table points to 1024 2nd level tables, which each consists of 1024 pages. We also know that an address space of [0, 1024KB] is 256 pages (1024KB/4KB=256). Thus, we only need one second layer table, and one first layer table to be able to map the entire addresss space. If we assume that the page entry size is 4B, then our total page table size needed in memory is $1024 * 4 + 1024 * 4$, which is 8192 bytes, much smaller than the one level paging system.

This idea can be extented to three level paging.

Three Level Paging

Sv39 is a three level paging architecture. Instead of repeating, lets just analyze why we should use a multi-level paging architecture.

Conclusion

Thanks for reading, hope you learned something!